Here’s how Malaysian companies are destroying rainforests abroad

6 天前

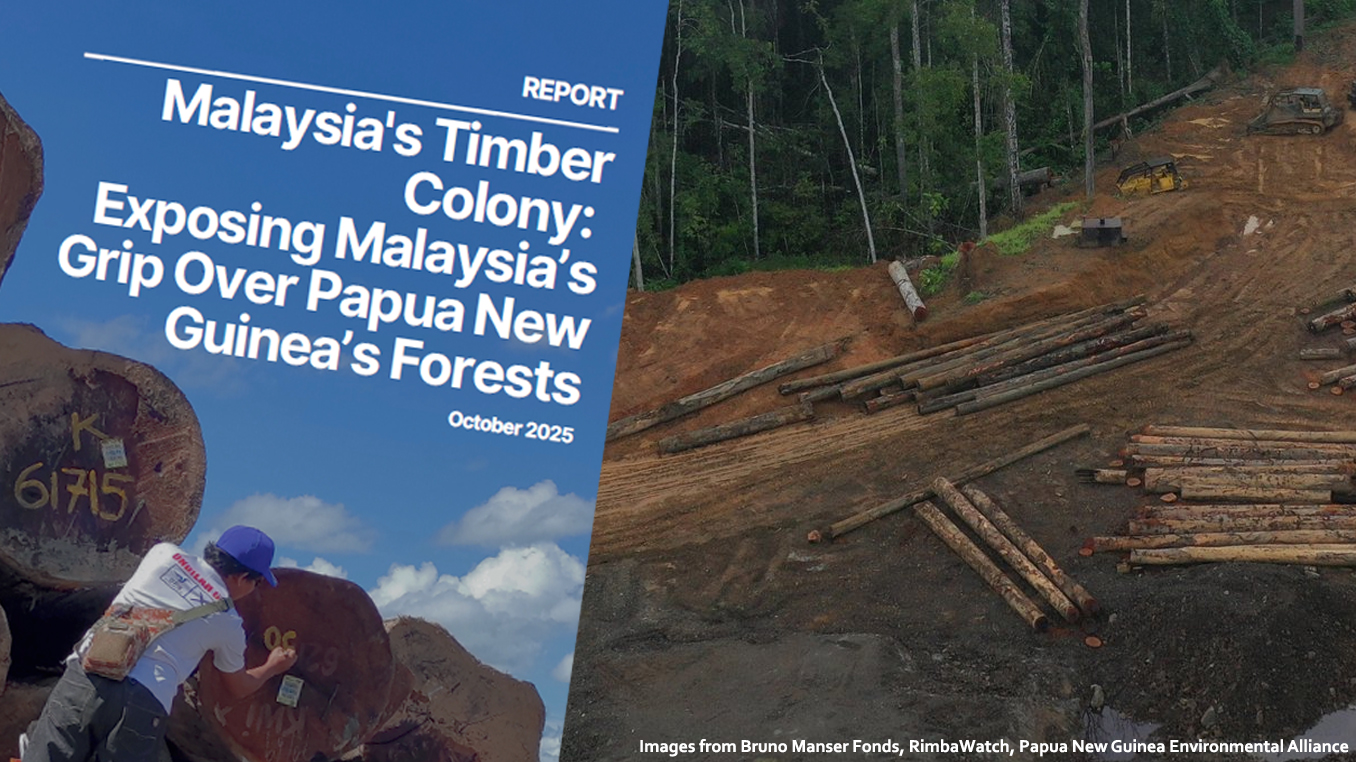

Recently, an environmental bombshell dropped on our doorstep, or rather, on Papua New Guinea (PNG)’s rainforests. Environmental groups Rimbawatch, Bruno Manser Fonds, and PNG Environmental Alliance released a 56-page report claiming that Malaysian companies are behind massive deforestation projects in the country. Because apparently, cutting down trees locally wasn’t enough, some Malaysian companies decided to expand their portfolio overseas.

So what exactly did the report find?

Aptly titled “Exposing Malaysia’s Grip over Papua New Guinea’s Forests”, the whole thing basically describes how 2-ish million hectares of PNG’s rainforest (roughly the size of Perak) are under threat from forest clearing licenses. If that wasn’t concerning enough, a whopping 97% of those are linked to Malaysians. And if that STILL wasn’t enough, these aren’t your everyday Malaysians either.

The cherry on top of this sad, overbaked cake is that there are some pretty well-connected names involved in this. We’re talking a Sarawak municipal councillor, a former senator, and even a Dato Sri who used to head the Sarawak Chinese Federation. We’ll be divulging everything we know about those guys in a bit, but first, how did Malaysians end up holding all these forest-clearing licenses in a country 3,000km away?

It all starts with how PNG’s land laws work (or don’t)See, in PNG, most land belongs to the indigenous people through what they call customary land. Basically, this means the land is owned collectively by local clans or tribes and passed down through generations. It also means the land is managed according to their own customs and traditions instead of government-issued titles or deeds.

So unlike Malaysia where land ownership is tied to formal documents (like a geran or strata title), in PNG, more than 90% of the land is just known to belong to the people who’ve lived there even if it’s not formally registered on paper. Which makes it a bit tricky for businesses, because one day you’re laying bricks and the next day someone could show up claiming it’s their great-grandfather’s backyard.

To get around this, the PNG government came up with something called the Land Act, which lets them lease customary land under a ‘Special Agricultural and Business Lease’ (or SABL). It’s a bit of a mouthful but think of it as a legal shortcut. It gives companies a temporary title so they can lease the land, while the original owners’ rights are put on pause for as long as the lease lasts. And yeah, if that sounds a bit scammy… it kinda is.

In the decade after SABLs were introduced, a bunch of companies that got these leases were dragged to court cos by law, landowners have to agree before anything happens. And, well, spoiler alert, many of them never did. Case in point, in 2013, a Commission of Inquiry looked into 72 SABLs and found that only four had real landowner consent and legitimate agricultural projects. It goes without saying that the rest of those were built on big fat nothing lies.

Which makes you wonder, if landowner approval is supposed to be a must…

How do PNG locals actually end up signing away their land?It usually starts with something that sounds pretty great.

Back in 2014, a local TV report showed a palm oil project in PNG that was being sold as a big opportunity for the locals. The pitch was simple. The community’s healthcare and schools were lacking, but if they agreed, the company would build roads, hospitals, schools, create jobs and so on, so forth. So memang lah the locals were excited. Heck, even the governor was on board.

And with that, the company in that 2014 video had everything lined up i.e. government blessing, landowner consent, and a shiny vision of development. All that was left was to clear the land for their palm oil plantation. To do that though, the company would need a special permit called a Forest Clearing Authority (FCA).

Now, if SABLs are like the main lease that lets companies use customary land for development, then the FCA is the permission slip to clear more than 50 hectares of forest for that purpose. Most importantly, FCAs are not meant for logging. That’s a whole different license called a Forest Management Agreement (FMA), which comes with more rules to make logging at least somewhat sustainable. FCAs are meant for clearing trees so you can grow something else, like crops or palm oil.

And this is where things started going downhill. Companies figured out they could use FCAs to log trees without dealing with all the mafan rules under proper logging permits. So instead of applying for an FMA and following sustainability guidelines, some companies just slap the word ‘agriculture’ on their proposals and call it a day.

NGOs have found plenty of red flags like project plans that were clearly unrealistic but still got approved, companies asking to clear way more land than they actually needed, or conveniently cutting only the expensive timber while leaving the rest behind. Worse still, FCAs technically require the cleared land to be used for agriculture or development but in many cases, that never happens. Some companies just take the logs and disappear. Others, when locals protest, allegedly bring in the police to shut them up, sometimes even violently.

And this is where Malaysia comes into play.

The ones cashing in the most from all this deforestation are… MalaysiansHold on to your hats guys cos according to the report, out of 67 Forest Clearing Authority (FCA) licenses in PNG, 65 of them – that’s 97% – are held by Malaysian-linked companies. Either the companies are subsidiaries of Malaysian firms, or their directors and shareholders are Malaysians (or living comfortably in Malaysia). Basically, if you threw a dart at a map of PNG, chances are you’d hit a forest whose logging license belongs to a Malaysian.

And when we say Malaysian, we don’t just mean random businessmen trying their luck overseas. The report identified 79 Malaysians involved and honestly, some of the names come with serious tea. For starters:

Then there are familiar names that have shown up in the Panama Papers (the leaked documents exposing wealthy individuals stashing money in offshore accounts to avoid taxes) including Chung Ching Ting, Ting Chiong Ming, and several others. Oh, and there’s also a Dato’ Sri currently being investigated by the MACC for a land corruption scandal in Sabah. Because ofc there is.

The report also found that many of these names trace back to Sarawak’s timber dynasties i.e. the same families that helped flatten large parts of Malaysia’s forests decades ago.

Together, these families make up 31% of the Malaysians involved, but control 60% of the licenses and nearly 80% of the total FCA area. And that’s not even counting those who’ve already had run-ins with PNG authorities. There’s a couple accused of illegal logging, one charged with fraud, another deported outright.

All in all, this isn’t a story about a few Malaysian businessmen cutting a few trees. These are the same timber giants that deforested Sarawak and who are now doing it all over again, just across the sea in someone else’s home. And the consequences are frankly horrifying.

In one FCA owned entirely by a Malaysian national, the report alleged that local landowners who refused to give consent were threatened with guns and even locked in a shipping container for up to a week. The same company allegedly paid police officers to intimidate villagers, with one victim saying he had his jaw, teeth, and mouth broken during the assault.

And now that we know how badly Malaysians have entrenched themselves in this mess, the next obvious question is…

Who’s gonna clean this up, and how?Well, the report does have a few ideas. Especially if your name spells out the Malaysian government.

First off, it called for the MACC to open investigations into the Malaysian companies named in the report. The idea is to check whether there was anything sus about how they entered PNG and if they’ve broken any of our own laws that apply overseas, like the Anti-Money Laundering, Anti-Terrorism Financing, and Proceeds of Unlawful Activities Act.

It also suggested that the government should strengthen protections for NGOs, activists, and media outlets since these are the people most likely to get slapped with lawsuits or threats when they expose corporate shadiness.

Then there’s the money trail. The report recommends that Bank Negara and the Securities Commission create a financing blacklist for companies caught violating Malaysia’s National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights. Meaning if you’ve been found guilty of human rights or environmental abuses, you don’t get to walk into a Malaysian bank and apply for another big fat loan.

There’s also this petition that the team behind the report have launched, calling for an end to deforestation in PNG and the cancellation of all existing FCAs. At the time of writing, it has just over 3,500 signatures. So that’s something for you to do, if you feel inclined to help in some way too.

Because ultimately, what’s happening here isn’t just the actions of a few Malaysians finding ways to exploit vulnerable communities living far away from us. It’s also a reflection of us as a society and as a country, and how we see ourselves standing in the eyes of the world.

...Read the fullstory

It's better on the More. News app

✅ It’s fast

✅ It’s easy to use

✅ It’s free